The Birdcage TUI

Mission control for less than dinner for two.

Somewhere inside every Winegard Carryout G2 is a 2013-vintage NXP Cortex-M4 running firmware 02.02.48, driving two Allegro A3981 stepper motors and a Broadcom BCM4515 DVB-S2 tuner through 12 submenus and over 100 undocumented commands. In 2026, it takes commands from a Python TUI built on Textual and doesn’t seem to mind.

Gabe Emerson (KL1FI) went first — publishing control scripts

for five different Winegard variants, proving that a $50–200 RV salvage yard dish could replace

a $500–2000 commercial amateur radio rotator. Chris Davidson (cdavidson0522)

figured out the G2’s RS-422 wiring and discovered azscanwxp — the firmware’s built-in radio telescope mode.

Birdcage is what happens when you take all of that and give it a proper interface.

Quick Start

Section titled “Quick Start”-

Clone and install (from the

tui/directory inside the Birdcage repo):Terminal window cd tui/uv sync -

Run in demo mode (no hardware required):

Terminal window uv run birdcage-tui --demo -

Connect to a real dish:

Terminal window uv run birdcage-tui --port /dev/ttyUSB0 --firmware g2

Five Screens

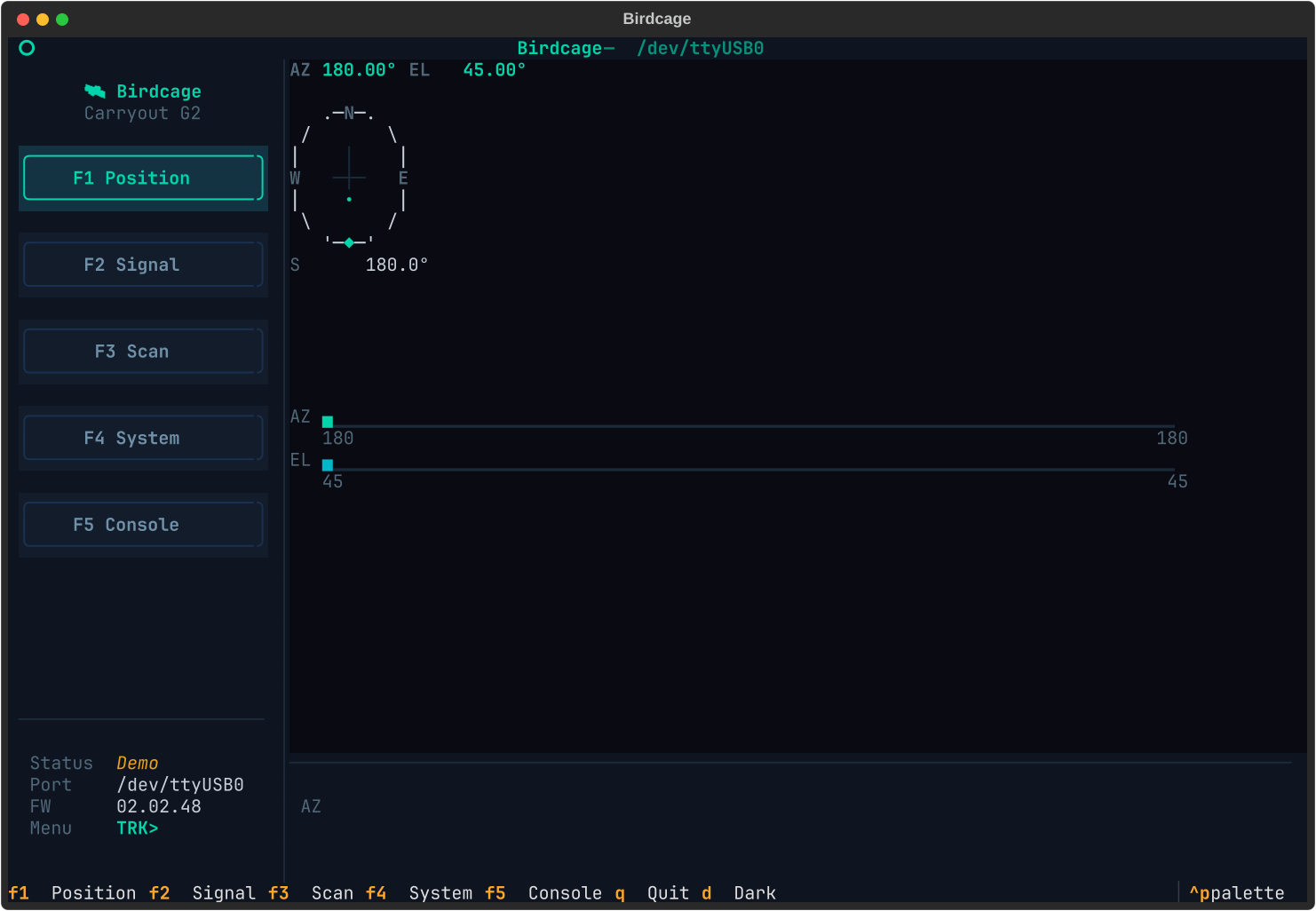

Section titled “Five Screens”Navigate between screens with F1–F5 keys or click the sidebar buttons. The device status bar at the bottom persists across all screens — connection state, serial port, firmware version, and current menu prompt are always visible.

F1 — Position

Section titled “F1 — Position”

The position screen is where you point the dish. A compass rose shows current azimuth with a bearing indicator, while AZ and EL sparklines track movement history over time. The numeric readout at top shows position to hundredths of a degree — the G2’s stepper resolution is 0.009° azimuth (40,000 steps/rev) and 0.014° elevation (24,960 steps/rev).

The AZ and EL sparklines give you immediate visual feedback: flat lines mean the dish is parked, slopes mean it’s slewing, and the amplitude of the noise floor after arrival tells you how much stepper backlash you’re dealing with.

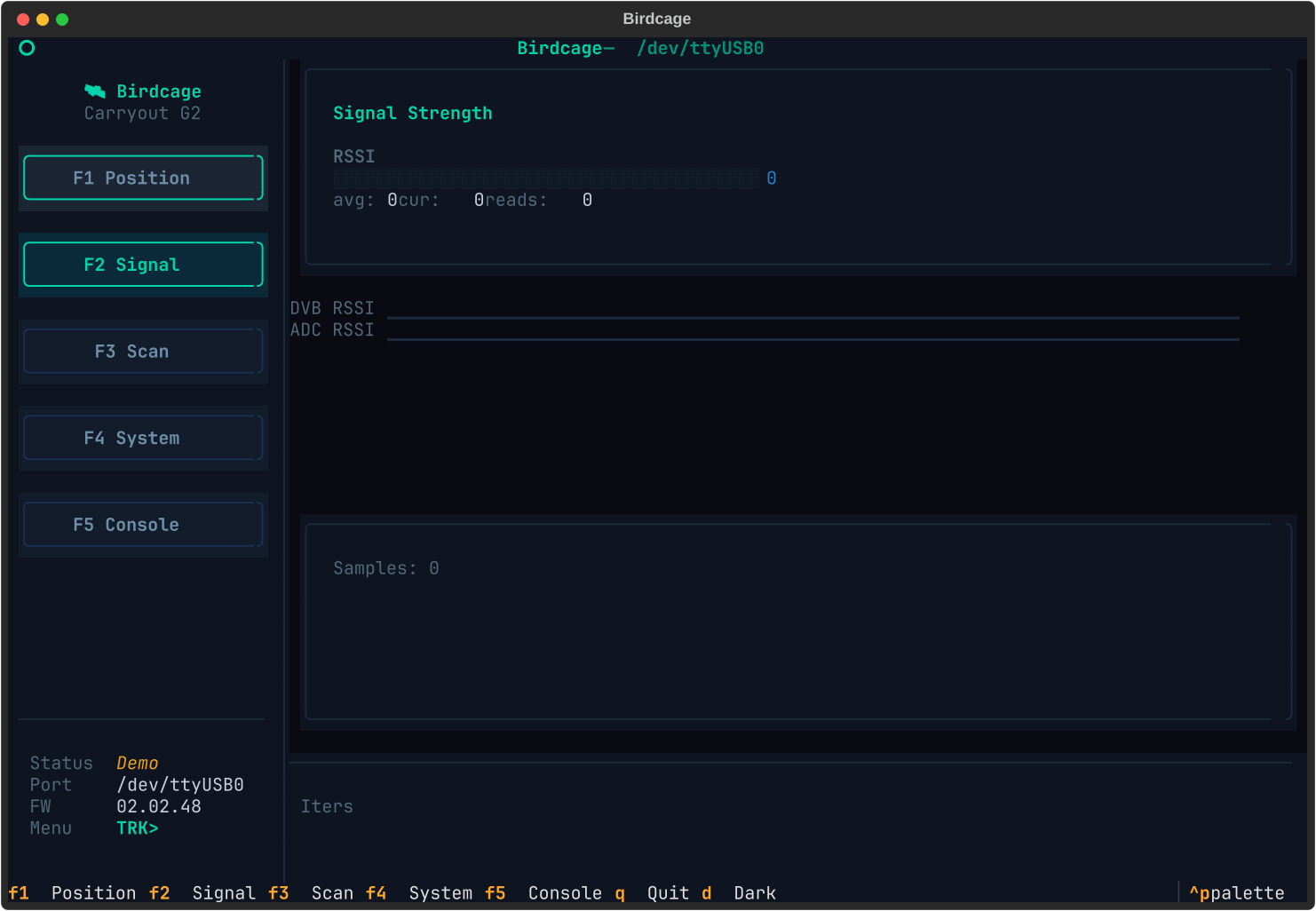

F2 — Signal

Section titled “F2 — Signal”

Signal strength from two sources: the BCM4515 DVB tuner’s RSSI (bounded, averaged) and the raw ADC reading (single-shot). The gauge uses sub-character Unicode block elements (▏▎▍▌▋▊▉█) for smooth visual resolution. Below the gauge, DVB RSSI and ADC RSSI sparklines show signal trends over time — useful for peaking during manual dish adjustment.

The sample counter and iteration display at bottom track measurement throughput. On a

live dish with the LNA enabled (lnbdc odu), you’ll see the noise floor sit around

RSSI 500 (ADC) or 230–490 (DVB, polarity-dependent).

F3 — Scan

Section titled “F3 — Scan”The scan screen wraps the firmware’s azscanwxp command — Davidson’s radio telescope

mode. Define an AZ×EL grid, set the step resolution, and watch the sky heatmap fill

in with RSSI-colored cells as the dish sweeps. Results export to CSV for post-processing

into proper sky maps.

F4 — System

Section titled “F4 — System”

The system dashboard. Top row shows the firmware identity banner: version 02.02.48, K60 MCU at 96 MHz, antenna ID “12-IN G2”. Below that, two side-by-side panels:

- A3981 Diagnostics — fault pin status for both stepper drivers (AZ/EL DIAG: OK or FAULT), plus step size mode (AUTO means the driver handles microstepping transitions automatically).

- Motor Dynamics — max velocity and acceleration for each axis. The G2 defaults to 65.0°/s azimuth, 45.0°/s elevation, with 400.0°/s² acceleration — fast enough to track LEO satellites at medium altitudes.

The NVS Table at the bottom is a scrollable browser of all 134 non-volatile storage values. Current, saved, and default columns let you see what’s been modified. The “Refresh NVS” and “Export NVS JSON” buttons at the bottom do what you’d expect.

F5 — Console

Section titled “F5 — Console”

Raw firmware console access with guardrails. Type commands directly to the dish’s serial

interface, see responses with color-coded prompt tracking (TRK>, MOT>, DVB>, NVS>,

etc.). Command history with up/down arrows.

The safety gates matter here: the console warns before sending q at root level (which

kills the firmware shell — requires power cycle to recover), before reboot, and before

NVS writes. The firmware doesn’t have an “are you sure?” prompt. Birdcage does.

Demo Mode

Section titled “Demo Mode”Pass --demo and Birdcage substitutes a DemoDevice for the serial bridge. The simulator models:

- Motor physics — position changes at ~10°/s with configurable settling noise (±0.05° random perturbation to simulate stepper backlash)

- RSSI signal — Gaussian model centered on a target position, so signal strength increases as you point closer to the simulated source

- All 12 submenus —

TRK>,MOT>,DVB>,NVS>,A3981>,ADC>,OS>,STEP>,PEAK>,EE>,GPIO>,LATLON>,DIPSWITCH>. Menu navigation withmot,dvb,nvs, etc. andqto go back all work correctly - Full NVS dump — the complete 134-entry table from firmware 02.02.48, captured from a live unit on 2026-02-12

Every screen, every widget, every button works in demo mode. It’s the same code path — the only difference is what’s on the other end of the bridge.

The Story

Section titled “The Story”The hardware was never the hard part. RV satellite dishes show up at salvage yards for $50–200 because the RV got totaled or the owner switched to Starlink. The mechanicals are built to survive highway speeds and hailstorms. The motors are Allegro A3981 stepper drivers with 1/16 microstepping — more precise than most amateur radio rotators at ten times the price.

The gap was always software.

Gabe Emerson (KL1FI) bridged it first. Five repositories for five Winegard variants — the

Trav’ler (HAL 0.0.00 and HAL 2.05), the Trav’ler Pro, the original Carryout, and the

Carryout G2. Python scripts that send a 0 180 to point azimuth south and a 1 45 to tilt

elevation to 45°. A rotctld bridge so Gpredict could drive the dish. Proof that the idea

worked.

Chris Davidson took the G2 further — mapped the RS-422 wiring (four wires, not two, and

polarity matters or you get garbled data at the correct baud rate), discovered the azscanwxp

command buried in the motor submenu, and turned a TV satellite dish into an RF imager.

Birdcage picks up where they left off. We reverse-engineered over 100 commands across 12 firmware submenus using automated probing and interactive exploration. We documented the full NVS table (134 entries), the GPIO pin map, the SPI bus layout (4 MHz to the motor drivers, 6.857 MHz to the DVB tuner), the DiSEqC 2.x interface, and the boot sequence from bootloader through motor calibration to prompt.

The TUI is what ties it together. Not because a terminal interface is fashionable, but because when you’re on a roof with a laptop and a USB-to-RS422 adapter, you want something that runs over SSH and shows you everything at once.

A 2013 microcontroller. A 2026 terminal. A dish that costs less than the cable to connect it.

That’s the project.